Science

Watch The Sun Briefly Pull Off The Devil Comet’s Tail

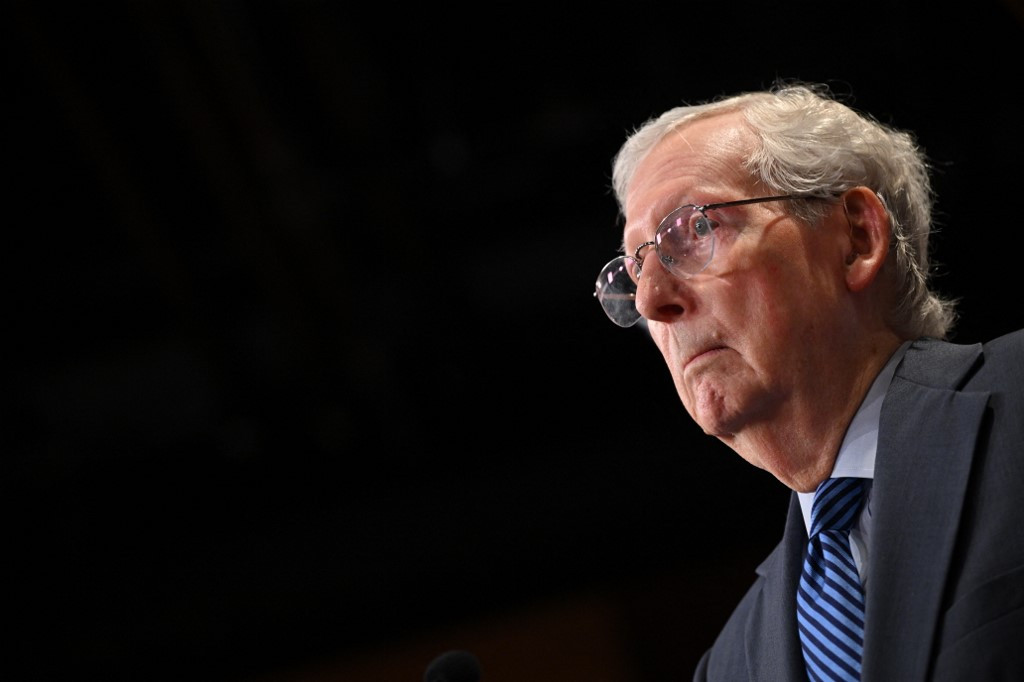

‘Tonight, Beijing and Moscow Are Watching Closely’

World

The US Senate voted 79-18 on Tuesday night to pass a $95 billion foreign aid bill, including a long-awaited $61 billion for …

Save up to 60% on watches at Amazon for Mother’s Day

LifeStyle

Mother’s Day is creeping up, but there’s still plenty of time to get Mom a really great gift. Sometimes, the perfect present …

‘Lost’ Gustav Klimt painting to be auctioned

Entertainment

By Bethany Bell BBC News, Vienna 8 hours ago Image caption, The painting is thought to depict a daughter of either Adolf …

Amazon grocery delivery subscription for Prime members, EBT customers

Business

Lee este artículo en español. Today, we are excited to launch a grocery delivery subscription benefit to Prime members and customers using …

Anne Hathaway’s Ex-Casting Directors Deny Chemistry Reads on Their Sets

Entertainment

Exclusive Anne Hathaway Casting Directors Deny Creepy Chemistry Read … Wasn’t Our Projects!!! 4/24/2024 12:40 AM PT Anne Hathaway claims she once …

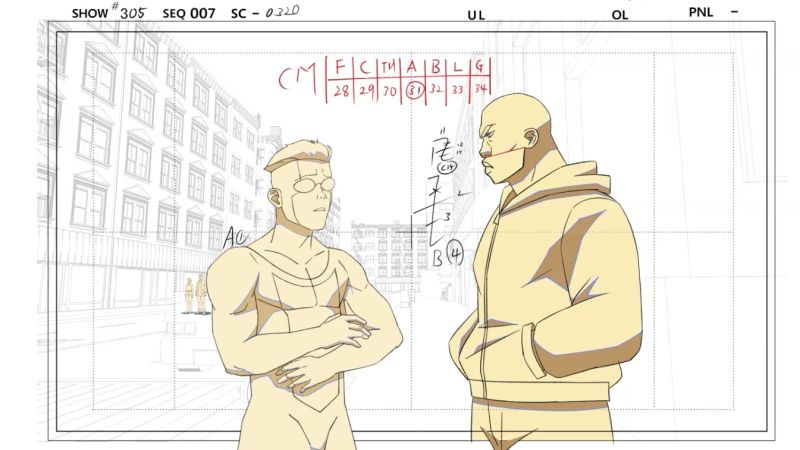

2024 NFL Mock Draft: Brinson’s Worst Mock Ever designed to anger every single NFL fan base

Sports

USC • Jr • 6’1″ / 215 lbs Projected Team Chicago PROSPECT RNK 1st POSITION RNK 1st PAYDS 3633 RUYDS 121 INTS …

131 million in U.S. live in areas with unhealthy pollution levels, lung association finds

Science

Nearly 40% of people in the U.S. are living in areas with unhealthy levels of air pollution and the country is backsliding …

A conservative quest to limit diversity programs gains momentum in states

Politics

A conservative quest to limit diversity, equity and inclusion initiatives is gaining momentum in state capitals and college governing boards, with officials …