Sports

Jaden Rashada announces transfer from Arizona State, 1 year after landing there in wake of Florida NIL fiasco

India votes in gigantic election as Modi seeks historic third term

World

* Indian election to last 7 weeks, has 968 mln voters * PM Modi expected to win a rare third term * …

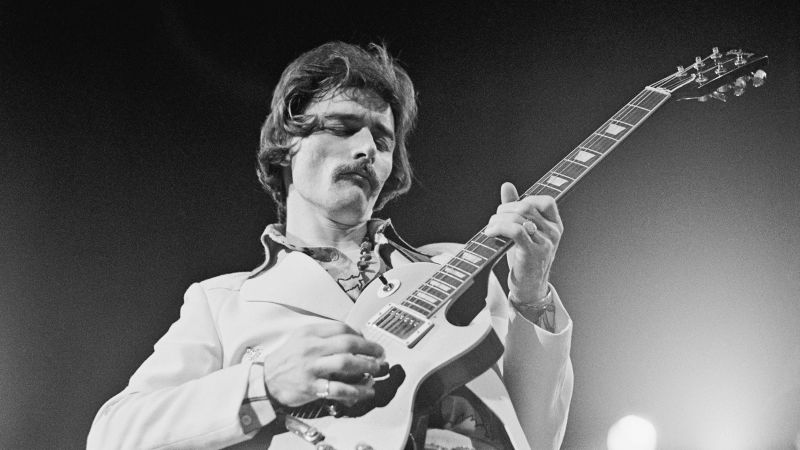

It took 20 years for Children of the Sun to become an overnight success

Technology

Children of the Sun burst onto the indie scene like a muzzle flash on a dark night. Publisher Devolver Digital dropped the …

Netflix explains decision to stop reporting crucial subscriber data

Business

Netflix (NFLX) will no longer report membership numbers starting next year — a bombshell move for the streaming industry, which has historically …

Who says soap operas are dead? ‘The Gates’ gives hope for genre’s revival.

Entertainment

For the first time in 25 years, a new daytime drama has entered production: The Gates — following the lives of a …

Your guide to Bulls-Heat & Kings-Pelicans

Sports

• Download the NBA App The 2024 NBA postseason tips off with the SoFi Play-In Tournament. Get ready for the action with previews and …

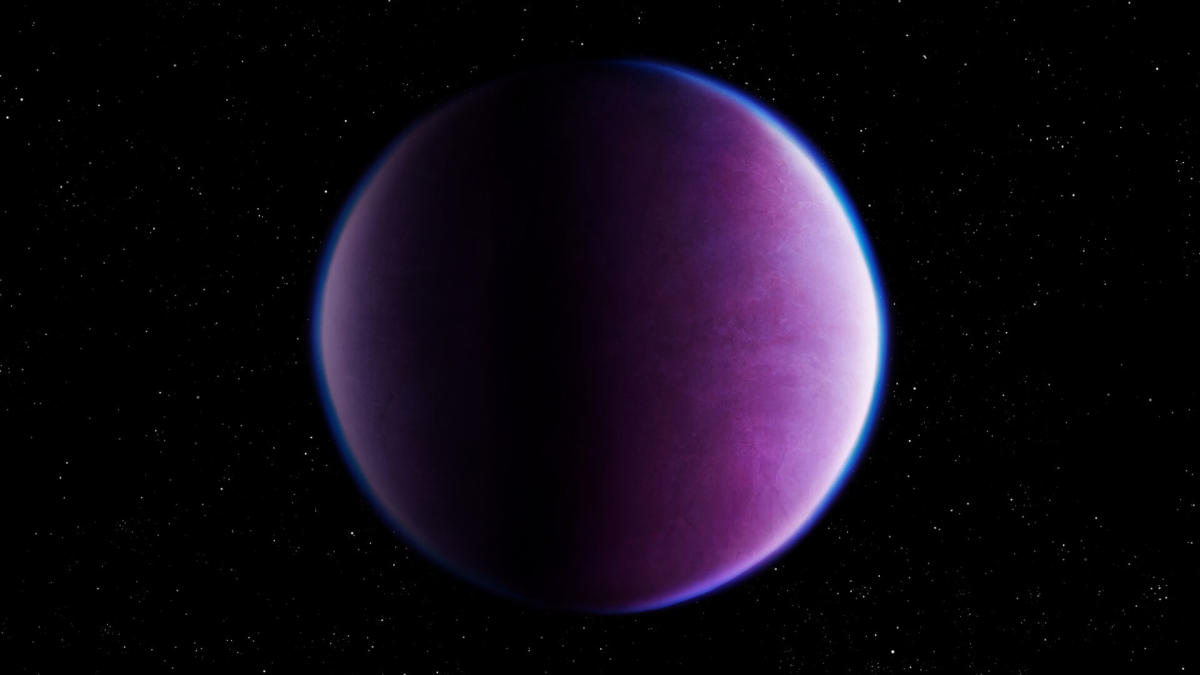

SpaceX launches Starlink satellites on company’s 40th mission of 2024

Science

SpaceX launched its 40th mission of the year this evening (April 18). A Falcon 9 rocket carrying 23 of the company’s Starlink …

Hospital prices for the same emergency care vary up to 16X, study finds

Health

Enlarge / Miami Beach, Fire Rescue ambulance at Mt. Sinai Medical Center hospital. ] Since 2021, federal law has required hospitals to …

Oviedo couple accused of using medical transport business to commit Medicaid fraud

U.S.

The owners of a Central Florida medical transportation company are facing allegations that they fraudulently billed the Medicaid program for more than …