Science

Russia launches new Angara A5 heavy-lift rocket on 4th orbital test mission (photos)

We Finally Know Where Neuralink’s Brain Implant Trial Is Happening

Technology

Elon Musk’s brain-implant company Neuralink has chosen the Barrow Neurological Institute in Phoenix, Arizona, as the initial study site to test its …

Bitcoin’s next ‘halving’ is right around the corner. Here’s what you need to know

Business

NEW YORK (AP) — Sometime in the next few days or even hours, the “miners” who chisel bitcoins out of complex mathematics …

Rebel Moon Part Two: The Scargiver Review

Entertainment

Rebel Moon Part Two: The Scargiver is now streaming on Netflix Rebel Moon creator Zach Snyder had hailed Part One: A Child …

2024 seven-round NFL Mock Draft: Patriots lean heavily on offense, Cardinals take opposite approach

Sports

For several months, NFL media has been focused on first-round mock draft projections but those are just 32 of the 257 names …

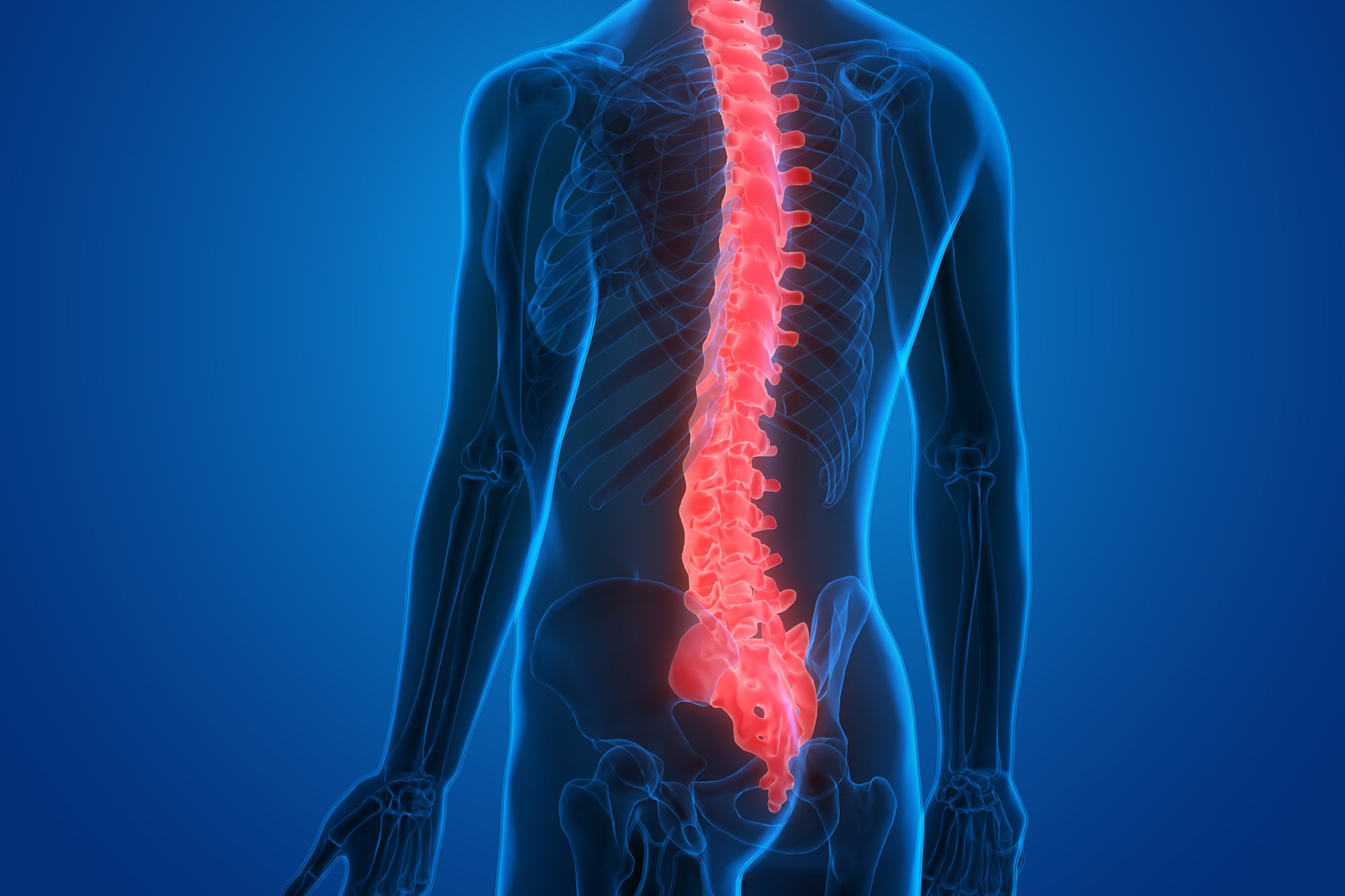

Remarkable Findings – New Research Reveals That the Spinal Cord Can Learn and Memorize

Science

New research demonstrates that the spinal cord can independently learn and remember movements, challenging traditional views of its role and potentially enhancing …

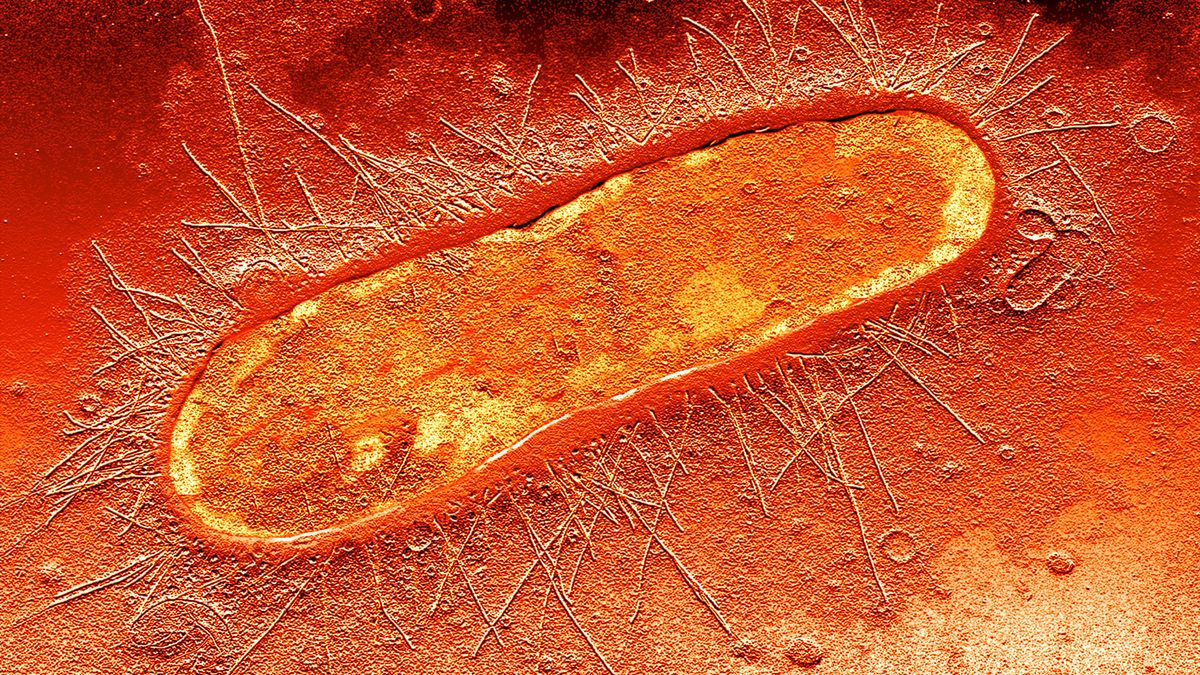

WHO Warns Growing Spread of Bird Flu to Humans Is ‘Enormous Concern’ : ScienceAlert

Health

The World Health Organization voiced alarm Thursday at the growing spread of H5N1 bird flu to new species, including humans, who face …

Over 100 arrested at Columbia University as police move in on pro-Palestinian protesters

U.S.

NEW YORK — Police arrested more than 100 people at Columbia University on Thursday at a makeshift encampment set up by pro-Palestinian …

Democrats help advance Ukraine, Israel aid in rare rules move

Politics

The House Rules Committee late Thursday night advanced a package of foreign aid bills — but only with help from Democrats who, in …