SALT LAKE CITY — Within a galaxy spanning many light-years and over 13 billion years old, it makes sense that major astronomical discoveries come few and far between — and that’s putting it lightly.

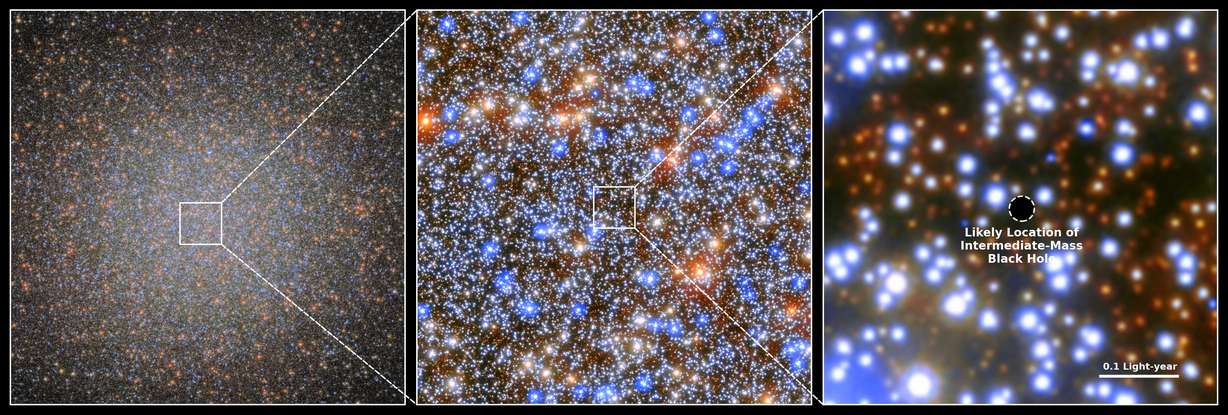

Nestled in the Milky Way is the Omega Centauri, a global cluster of millions of stars — so dense toward the center, it becomes impossible to distinguish individual stars — only visible as a small speck in the night sky from southern latitudes.

But within that cluster is something astronomers have sought for and argued over nearly a decade, and something a new study led by researchers from the University of Utah and the Mac Planck Institute for Astronomy uncovered: Omega Centauri is home to a central black hole.

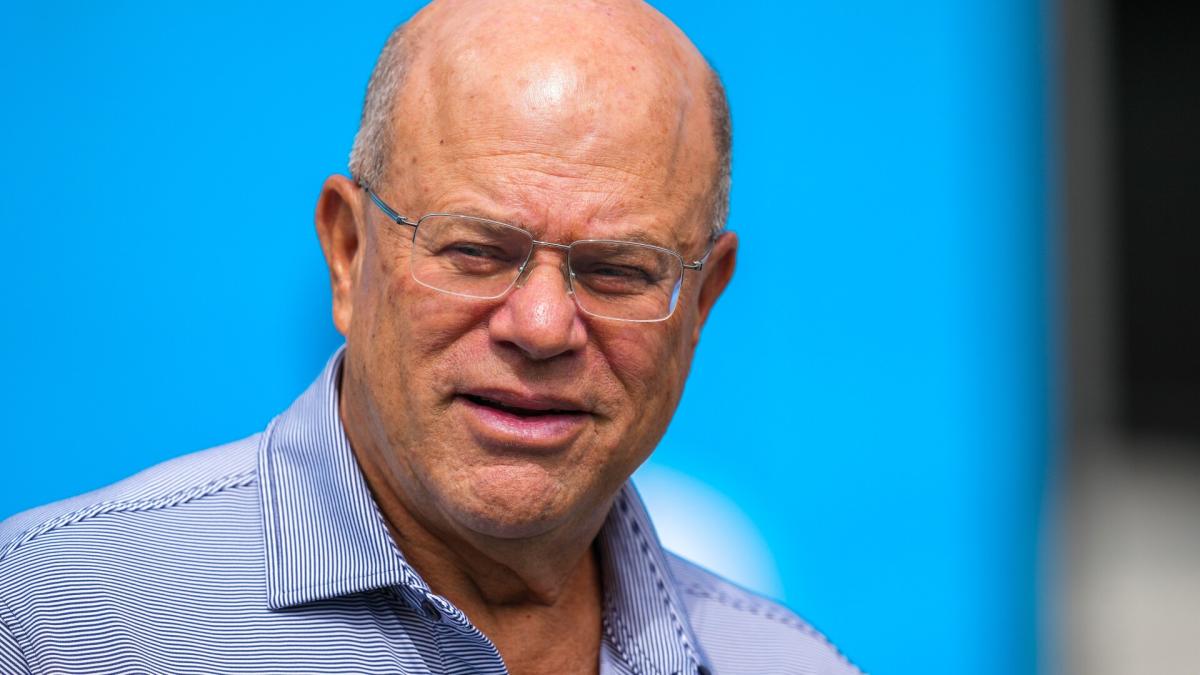

“This is a once-in-a-career kind of finding. I’ve been excited about it for nine straight months. Every time I think about it, I have a hard time sleeping,” said Anil Seth, associate professor of astronomy at the U. and co-principal investigator of the study.

‘On the level of Bigfoot’

The study, which was published in the journal “Nature” on Wednesday, explained that black holes come in different mass ranges.

Common black holes include stellar black holes, ranging between one to a few dozen solar masses and supermassive black holes, with masses of up to billions of suns.

More notoriously elusive with no definite detections — until now — are intermediate-mass black holes, the kind discovered by the research team.

“These intermediate-mass black holes are kind of on the level of Bigfoot. Spotting them is like finding the first evidence for Bigfoot — people are going to freak out,” said Matthew Whittaker, an undergraduate student at the U. and co-author of the study.

‘Needle in a haystack’

Omega Centauri appears to be the core of a small, separate galaxy that had its evolution cut short when it was swallowed by the Milky Way, the paper states. The current state of galaxy evolution suggests these earliest galaxies should have had intermediate-sized central black holes that would have grown over time.

But how do you go about finding one?

Seth and Nadine Neumayer, a group leader at the Max Planck Institute and principal investigator of the study, first began researching how to better understand the formation history of Omega Centauri in 2019.

They realized if they found fast-moving stars around its center, they could finally settle the question’s surrounding the cluster’s central black hole by measuring the black hole’s mass.

This search for the stars fell into the lap of Maximilian Häberle, a doctoral student at the Max Planck Institute. Häberle led the charge of developing a gargantuan catalogue for the motions of stars in Omega Centauri, measuring the velocities for 1.4 million stars by studying over 500 Hubble images of the cluster.

The challenge with this was that most of the images Häberle had at his disposal were taken to calibrate Hubble’s instruments, not to aid groundbreaking scientific discoveries.

Still, with over 500 images, this unintentional dataset served its purpose.

“Looking for high-speed stars and documenting their motion was the proverbial search for a needle in a haystack,” Häberle said. In the end, Häberle not only had the most complete catalog to date of the motion of stars in Omega Centauri, he also found seven needles in his archival haystack — seven fast-moving stars in a small region in the center of Omega Centauri.

The discovery

The work didn’t end with finding these seven stars, however. With seven stars, all with different speeds and movement directions, the researchers were able to separate the different effects and determine there, in fact, is a central mass in Omega Centauri, with the mass of at least 8,200 suns.

Furthermore, the images don’t suggest any visible objects at the location of that central mass as is expected for a black hole.

And more analysis led to more good news for the team. As the paper explained, a single high-speed star in the image might not belong to Omega Centauri. It could be a star outside the cluster that passes right behind or in front of Omega Centauri’s center by chance. The observations of seven such stars, on the other hand, can’t be coincidence and leave no room for explanations other than the presence of a black hole.

Checkmate.

Moving forward

The team now plans to build off its monumental findings by further examining the center of Omega Centauri. Seth is leading a project that gained approval to utilize the James Webb Space Telescope to measure the high-speed stars’ movement toward or away from Earth.

As future instruments roll out that could pinpoint stellar positions with even more accuracy than Hubble, the goal is to determine how the stars accelerate and how their orbits curve — though, that project will fall into the hands of future generations of researchers.

Still, this discovery builds the case for Omega Centauri as the core region of what once was a galaxy engulfed by the Milk Way billions of years ago.

For people interested in hearing directly from the researchers, Seth will present the team’s findings on Aug. 8 at 7 p.m. at the Clarke Planetarium IMAX theater in Salt Lake City. In the meantime, the full study can be found online.

“I think that extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence. This is really, truly extraordinary evidence,” Seth said.

Dr. Sarah Adams is a scientist and science communicator who makes complex topics accessible to all. Her articles explore breakthroughs in various scientific disciplines, from space exploration to cutting-edge research.