In January, 1972, Shirley Chisholm, the first Black woman elected to Congress, appeared at a Baptist church in Brooklyn and announced her candidacy for President of the United States. Chisholm was a singular force in American politics of the time: her support for civil rights and legal abortion made her a pivotal connection between the interests of African Americans and the emerging, mostly white, reproductive-rights movement. But, despite her status as a trailblazer, her campaign—set against an entirely white, entirely male field of rivals for the Democratic Party’s nomination—was more often than not treated as a lark. The newly formed Congressional Black Caucus, of which she was a founder, did not endorse her. (Many members chose to support George McGovern, the eventual nominee.) The political calculations were clear: the nation would not support a Black woman, and the better play was to back a viable candidate who might eventually provide a return on the investment.

Fifty-two years later, Kamala Harris’s ascent to being the presumptive nominee of the Democratic Party represents, on many levels, a sharp contrast to Chisholm’s story. (Harris, during her 2020 Presidential run, nodded to her predecessor’s significance by incorporating a color scheme and typography similar to Chisholm’s 1972 campaign materials into her own.) Chisholm waged a shoestring effort, using her own savings to keep her campaign afloat; for Harris, word of President Joe Biden’s exit from the race unleashed a torrent of cash to support her candidacy. ActBlue reported a hundred-and-five-million-dollar haul within roughly the first twenty-four hours. The next day, Voto Latino committed to forty-four million. Chisholm essentially had to build her own electorate as she campaigned; Harris’s entry into the Presidential contest sparked a reported seven-hundred-per-cent increase in voter registrations.

Yet, as various Democratic factions were defecting from Biden’s camp in the weeks after his disastrous debate with Donald Trump, the C.B.C. remained steadfast in its allegiance to him. This was understood as a product of Biden’s strong support among the caucus’s (largely Black) constituents. But had the C.B.C.—which Harris had belonged to as a senator—called for Biden to step down, it could have been cynically read as an attempt to engineer an opening for her. The caucus endorsed Harris soon after Biden withdrew, though, in essence declaring that, unlike in 1972, a Black woman candidate could be more viable than two white men: the incumbent and his opponent.

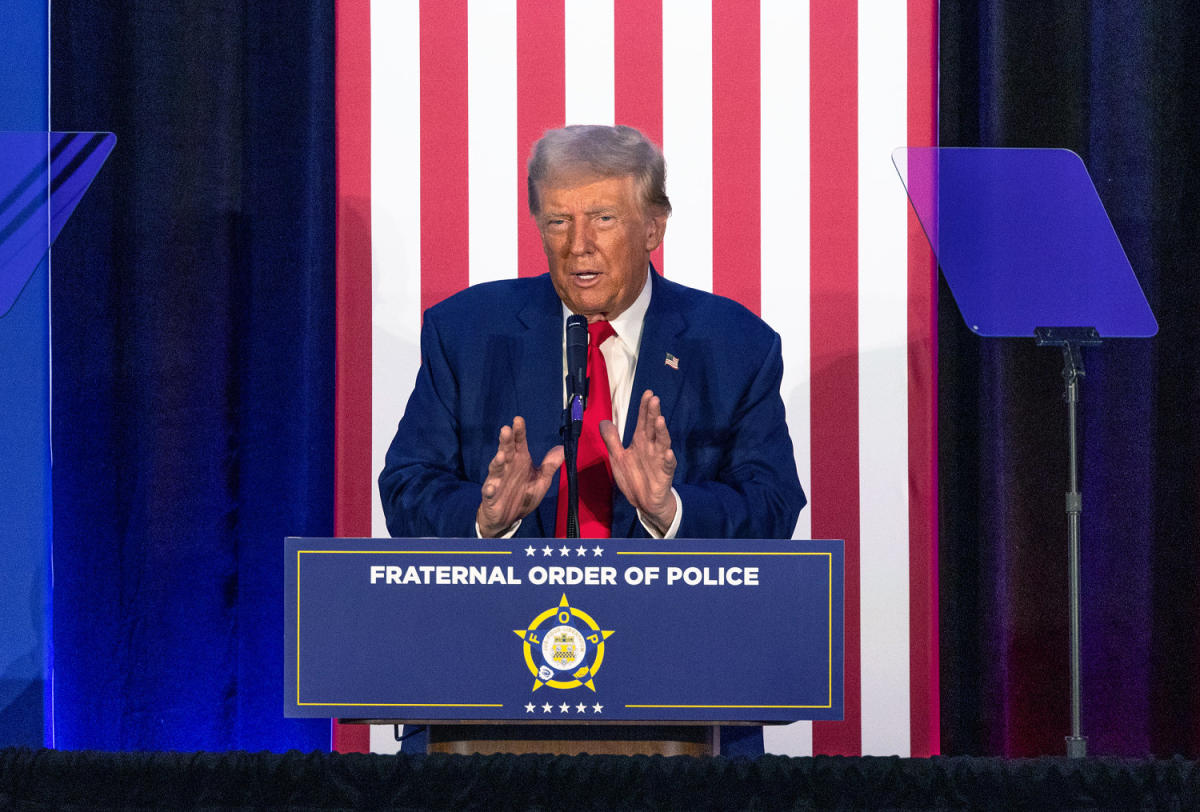

But we have not entirely broken with hidebound, stagnant tradition. In 2008 and 2016, the Democrats offered up barrier-breaking nominees for the Presidency; the Party is batting .500 when it comes to actually electing such candidates. Barack Obama’s 2008 campaign inspired poetic musings about shaking off the moribund strictures of race, even as the first ripples of the eventual tide of racial backlash could be felt virtually from the outset. Hillary Clinton’s 2016 campaign was confronted with an unending assault of unfounded rumors, sexist insinuations, and conspiracy theories; Clinton spent far more time on defense than any successful candidate could. This year, we find ourselves yet again questioning the durability of outmoded presumptions about race and gender. It’s as if the nation has been running an experiment in which, at eight-year intervals, we test the impact of different kinds of identities in national elections. The constant in this experiment has been Trump. Amid the myriad provocations that he has authored, it’s easy to forget that his political career began with a campaign to convince the public that Obama was not born in the United States. Trump moved on to the high-volume mendacity and misogynistic contempt that characterized not only the 2016 campaign but also the Presidency it delivered to him. The past week has seen him awkwardly trying to figure out how to hate Harris from scratch.

Meanwhile, Trump-era reactionaries have waged cultural warfare against “critical race theory,” while acting in ways that make that school of thought only more relevant. The legal scholar Kimberlé Crenshaw’s ideas about intersectional feminism—that the nexus of race and gender produces a complicated synergy—could not be more central to this election. This week, Representative Tim Burchett referred to Harris as a “D.E.I. Vice-President.” It was a feckless jab that presumed that there is something shameful about operating in arenas where people like you have traditionally been excluded, but it also disregarded the fact that Harris has years more experience in elected office than Trump and his running mate, Senator J. D. Vance, combined. A deluge of memes has taken aim at the Vice-President’s personal life and dating history. Yet such assaults betray a transparent desperation—feeble barbs hurled from the mezzanine. There is reason to believe that more mature, humane voices will prevail, or, at least, that they’ll now have a fighting chance.

On Monday night, fifty-three thousand Black men joined a virtual rally hosted by the journalist Roland Martin. Trump’s potential appeal to working-class Black men has been a constant sub-theme in the contest. In the course of four hours, guests including Senator Raphael Warnock, Representatives Gregory Meeks and Steven Horsford (the C.B.C. chair), Governor Wes Moore, the actor Don Cheadle, the Reverend William Barber, and a host of state and local officeholders gave brief speeches explaining the imperative to support Harris’s candidacy. The event followed one of similar size held the previous night for Black women voters, and preceded others targeting Latinos, South Asians, and white female voters on successive nights this week.

The digital rallies were notable for several reasons, not the least of which was the more than ten million dollars in donations they brought in. What is perhaps more important is that they reckoned with the social complexities of a campaign such as Harris’s. Speaker after speaker on the Monday call warned against the sexism that might make it difficult for some men to imagine Harris as the President. The event on Thursday brought together more than a hundred and fifty thousand white women and pointed to barriers that have historically divided women along racial lines. The following morning, Barack and Michelle Obama endorsed Harris. These developments demonstrated an awareness of what was lost when people shrugged off Shirley Chisholm’s candidacy.

On Monday, just ahead of the Black men’s rally, Harris gave a speech in Indianapolis in which she took aim at her G.O.P. opponents, saying, “These extremists want to take us backward, but we are not going back.” The words resonated, and crowds have now taken to chanting them at Harris’s events. She was referring to the days of “chaos” that characterized Trump’s Presidency, but she could just as well have been talking about the days when a candidacy like hers would not have been able to make it as far as it already has. ♦

Amanda Smith is a dedicated U.S. correspondent with a passion for uncovering the stories that shape the nation. With a background in political science, she provides in-depth analysis and insightful commentary on domestic affairs, ensuring readers are well-informed about the latest developments across the United States.