2022 was the bad year that wasn’t—at least for a mysterious paralyzing condition in children.

In the decade before, hundreds of young, healthy kids in the US abruptly felt their limbs go weak. Debilitating paralysis set in. In recent years, around half of affected children required intensive care. About a quarter needed mechanical ventilation. A few died, and many others appear to have permanent weakness and paralysis.

Researchers quickly linked the rare polio-esque condition to a virus known for causing respiratory infections, often mild colds: enterovirus D68, or EV-D68 for short. Identified decades ago, it’s a relative of polio, one of the over 100 non-polio enteroviruses that float around. But when EV-D68 began surging, so did the mysterious paralyzing condition, called acute flaccid myelitis, or AFM. The menacing pair seemed to come in waves every other year, likely starting with a cluster of cases in California in 2012. In 2014, there were 120 AFM cases in 34 states. In 2016, 153 cases in 39 states. In 2018, 238 cases in 42 states. By contrast, there were just a few dozen cases or so in each of the years in between, cases that were sporadic or unrelated to EV-D68.

2020 was the next year to watch, but SARS-CoV-2 came crashing in. Amid shutdowns, masks, distancing, and heightened hygiene, the pandemic obliterated normal transmission cycles of many other pathogens. EV-D68 was no exception. So researchers looked to 2022. At that point, there would be a four-year gap since the last EV-D68 surge, not the normal two-year gap. The pool of young children who had not been exposed to a recent wave of EV-D68 would be even larger than usual. They seemed like sitting ducks.

“Although the exact timing of the next enterovirus D68 outbreak is difficult to predict, large outbreaks of enterovirus D68, and therefore acute flaccid myelitis, are likely to be imminent,” US researchers warned in a commentary published in The Lancet Microbe on January 7, 2022.

In the summer, EV-D68 began rising. Its spread looked to rival what was seen in 2018, when there were 238 AFM cases. The EV-D68 strain circulating was similar to the 2018 strain, too. In early September, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention sent a warning to clinicians through its Health Alert Network: EV-D68 is rising around the country. Be on the lookout for AFM. It’s coming.

But it never came. Though the EV-D68 wave came and went, AFM cases stayed low. Looking at the percentage of kids with a respiratory illness who were positive for EV-D68, transmission in 2022 appeared to be even higher than it was in 2018. As expected, the virus came roaring back after its pandemic break. But there were only 47 cases of AFM that year, not hundreds. It was an off-year for the condition.

So what happened? Why didn’t AFM surge along with EV-D68? In short, no one knows.

Pleasant surprise, lingering mystery

“It’s surprising, totally,” Matthew Vogt, a pediatric infectious disease expert at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, told Ars. He noted that he was among the authors of the January 2022 commentary in The Lancet Microbe. “I was on record, really thought I understood what was happening, and I was wrong… I thought we were going to have a bad outbreak in 2022.”

It’s yet another riddle swirling around AFM. Why did EV-D68 start causing national surges in 2014? Why do most children with EV-D68 get a mild respiratory infection and recover, while an unlucky few develop paralysis in the days afterward? And a pressing question now: What comes next?

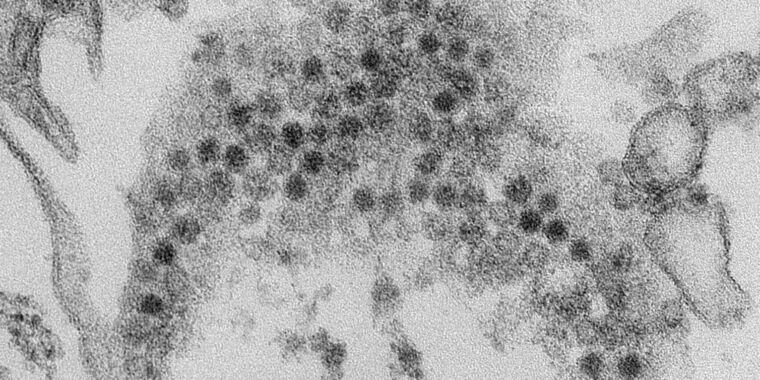

In May of 2022, Vogt, along with colleagues, published damning evidence that EV-D68 is behind some AFM cases. The study, appearing in the New England Journal of Medicine, found genetic material (RNA) and proteins from EV-D68 in motor neurons in the spinal cord of a 5-year-old boy who tragically died of an AFM-like illness in 2008. Until then, the virus had been hard to pin down in the central nervous system, rarely showing up in cerebrospinal fluid—which is the case for polio virus as well.

Rachel Carter is a health and wellness expert dedicated to helping readers lead healthier lives. With a background in nutrition, she offers evidence-based advice on fitness, nutrition, and mental well-being.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/Bad-Drinks-You-Shouldnt-Avoid-for-Weight-Loss-ed7c65a1ab9d47c882a810beda2a97f6.jpg)