In the summer of 2022, a family gathered in South Dakota for a reunion that included a special meal—kabobs made with the meat of a black bear that one of the family members had “harvested” from northern Saskatchewan, Canada, that May. Lacking a meat thermometer, the family assessed the doneness of the dark-colored meat by eye. At first, they accidentally served it rare, which a few family members noticed before a decision was made to recook it. The rest of the reunion was unremarkable, and the family members departed to their homes in Arizona, Minnesota, and South Dakota.

But just days later, family members began falling ill. One, a 29-year-old male in Minnesota, sought care for a mysterious illness marked by fever, severe muscle pains, swelling around his eyes (periorbital edema), high levels of infection-fighting white blood cells (eosinophilia, a common response to parasites), and other laboratory anomalies. The man sought care four times and was hospitalized twice in a 17-day span in July. It wasn’t until his second hospitalization that doctors learned about the bear meat—and then it all made sense.

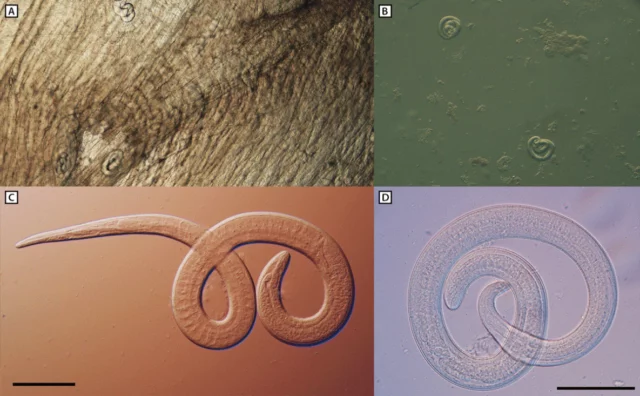

The doctors suspected the man had a condition called trichinellosis and infection of Trichinella nematodes (roundworms). These dangerous parasites can be found worldwide, embedded into the muscle fibers of various carnivores and omnivores, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. But, it’s quite rare to find them in humans in North America. Between 2016 and 2022, there were seven outbreaks of trichinellosis in the US, involving just 35 cases. The majority were linked to eating bear meat, but moose and wild boar meat are also common sources.

Once eaten, larvae encased in the meat are released and begin to invade the small intestines (the gastrointestinal phase), causing pain, diarrhea, nausea, and vomiting. Then, the larvae develop into adults in the gut, mate, and produce more larvae there. The second generation of worms then go wandering through the lymphatic system, into the blood, and then throughout the body (systemic phase). The larvae can end up all over, reaching skeletal muscles, the heart, and the brain, which is rich in oxygen. The systemic phase is marked by fever, periorbital edema, muscle pain, heart inflammation, and brain inflammation. The larvae can also provoke severe eosinophilia, particularly when they move into the heart and central nervous system.

The man’s symptoms fit the case, and several tests confirmed the parasitic infection. Of eight interviewed family members present for the bear-meat meal, six people had illnesses matching trichinellosis (ranging in age from 12 to 62), and three of them were hospitalized, including the 12-year-old. Four of the six sickened people had eaten the bear meat, while two only ate vegetables that were cooked alongside the meat and cross-contaminated. Experts at the CDC obtained leftover frozen samples of the bear meat, which revealed moving larvae. Testing identified the worm as Trichinella nativa, a species that is resistant to freezing.

In an outbreak study published Thursday in the CDC’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, health officials from Minnesota and the CDC reported that the three hospitalized patients were treated with the anti-parasitic drug albendazole and recovered. The remaining three cases fortunately recovered without treatment. The health experts noted how tricky it can be to identify and diagnose these rare cases but flagged periorbital edema and the eosinophilia as being key clinical clues to the grizzly infections. And, above all, people who are going to eat wild game meat should invest in a meat thermometer and make sure the meat is cooked to at least ≥165° F (≥74° C) to avoid risking brain worms.

Rachel Carter is a health and wellness expert dedicated to helping readers lead healthier lives. With a background in nutrition, she offers evidence-based advice on fitness, nutrition, and mental well-being.