In the darkness I maneuvered my body out of bed. I had been up a long time, well before the birds now starting to chirp outside my window. Ignoring my doctor’s nothing-by-mouth-after-midnight orders, I ate some cereal and drank a little milky-sweet coffee. I’m generally not a rule-breaker. But I couldn’t tolerate for the next six hours the hunger that comes with the last stages of pregnancy.

My husband brought the car around to the front of the house. Knowing that my baby’s first cry would reverberate through the world before noon was strange and scrumptious. I was four months shy of 46; this child would be my third and last. It was late to be having a baby—I knew I was tempting fate. Women of advanced maternal age often have complications. But so far, we had cleared all the hurdles, my baby and I. The ultrasounds, genetic testing, and amniocentesis gave me hope that the baby would be healthy. For my part, I passed with flying colors the screens for gestational diabetes and hypertension. We just had to get through the last and biggest step: childbirth.

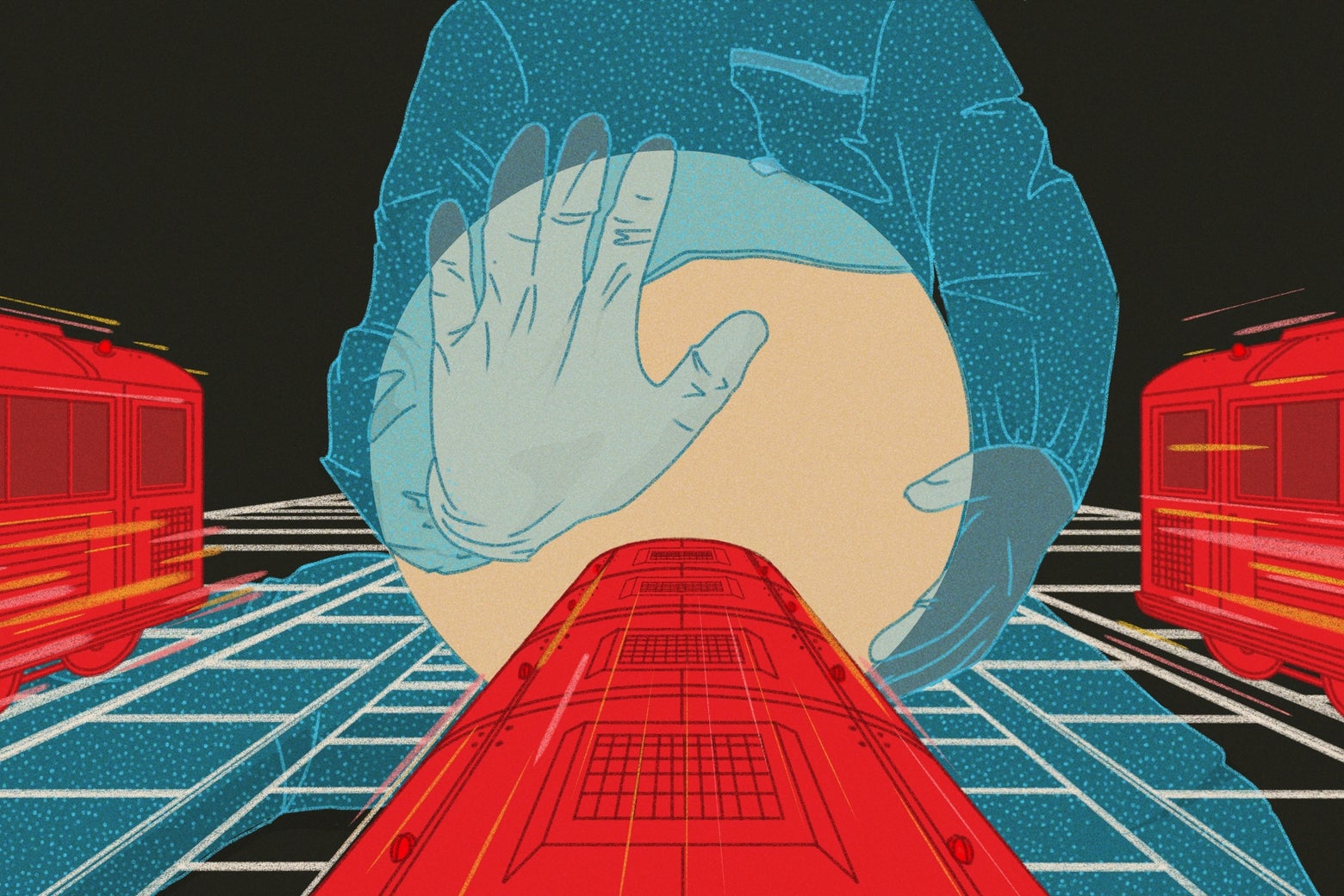

To mitigate risk, I had passed over the community hospital two blocks from me, deciding instead on an OB-GYN at the vast academic center miles away. “Why do you choose to schlep so far?” my friends kept asking. I imagined they probably thought me to be a touch crazy, with my enormous belly and swollen legs, riding the packed subways, standing all the way. My instincts just said this was the right choice. Go far, for the baby’s sake. It was the hospital where I had become a doctor myself, first starting as a lab tech, then a med student, then a resident, and finally an attending. I had toiled there for years, and I knew how it worked inside out.

Giving birth at 45 is rolling the dice. In my 30s, I believed in the promise of medical science’s overcoming many age-old biological hurdles, including the unforgiving female reproductive window. The stark reality is that aging is a hard stop that can’t be undone, only pressed against. Even though my last eggs could be milked out with IVF, they were still old eggs. And the body that needed to carry the fetus to term? Well preserved, but past peak for childbearing. Childbirth and AMA (the medical shorthand for women of advanced maternal age, which starts at 35) are an uneasy combination. For all our ideas about how our lives should or could be set up, mucking with nature comes with a disclaimer, written in fine print. Of course women are better off now for the choices we have—my life is, hands down, more navigable than it would have been if I’d had kids earlier. Putting it off allowed me to have my career. But I didn’t yet know what the cost of that choice would be.

In some ways, I didn’t have any other choice. I was late in realizing I wanted to be a doctor; it was not until a skiing accident in the mountains of Hokkaido, Japan—at the age of 25—when the dream took hold. At the time, I was an expat in Tokyo in a job that had me traveling the world. Despite the excitement, I was still, in the back of my mind, searching for one of life’s holy grails: a profession that would give meaning to my days. I figured it out when I watched my orthopedic surgeon fix my knee (I mean literally watch—he let me view the monitor during the arthroscopic procedure). After 10 years of studying and training, I became a doctor. I don’t know if I could have done it if I had been a mother too.

But giving birth at my age was going to mean reckoning with the consequences. Emergency medicine doctors like me see unimaginable things, so we usually have a backup plan. Mine was to deliver at the best hospital possible.

“Nervous?” Joe, my husband, asked as we drove in for the scheduled surgery for baby No. 3.

“I’m OK,” I said.

Joe is the kind of person who is calm in high-stakes moments. Seven years my junior, he has a fun-loving, risk-taking appeal that charmed me when we met 21 years ago, when I was in med school. He would spend a Tuesday night in a Chinatown bar, DJing Balkan music into the wee hours, and drag himself to his day job in the morning. I, on the other hand, spent every spare moment jamming endless lists of facts into my brain.

“Did I ever tell you that story from residency?” I said, passing the time in the car. “There was this woman.”

She was flying up the ladder in her career, and was, like me, the mother of small children. After delivering her baby, she started bleeding, and despite efforts to stop it, she continued to hemorrhage. Her team couldn’t save her. We were stunned. No one expects a healthy woman in the hands of the most advanced health care system in the world to die in childbirth.

But they do, and with more frequency, not less. There were 1,205 maternal deaths in 2021, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, or 33 per 100,000 births, up from 24 the year prior—a startling trend. Among developed nations, the U.S. has the highest maternal mortality rate. The MMR for women 40 and over is almost eight times what it is for women under 25. More women are having children later, and the age-related decline of the body leads to more adversities, complications, and, occasionally, even death during pregnancy and childbirth.

Silence for a moment. Then, from Joe: “Why talk about this now?”

We checked into the ward; I changed into a drafty hospital gown and walked into the cold operating room. They placed me onto the hard table, tying my wrists to arm boards set at 90 degrees to the table. Has anyone else ever noticed these crucifix vibes? I wondered. Joe entered gingerly in a quail egg–blue jumpsuit and bonnet and sat down next to me. The anesthesiologist discreetly put up a barrier, blocking our view of my gravid belly.

Everyone, correctly, ignored me and my mess. The baby mattered more.

It was supposed to be a routine C-section. My previous two babies had been surgical deliveries, meaning this one would be too: Once you step onto the C-section conveyor belt, you are almost certainly not getting off. Obstetricians are skittish about allowing a woman to labor hard after a C-section. In the throes of labor, a post-C-section uterus, whose mighty task is to expel the fetus, risks rupturing through the old incision. During my early medical training, I had assisted in C-sections. Parts of this surgery are enough to flip a strong stomach—even that of an aspiring doctor. How barbaric, I remember thinking long ago.

My surgery began. Though I couldn’t see or feel anything, I could hear, smell, and imagine. I followed along in my head as they cut through the layers of my abdomen: first skin, then fat, fascia, and finally muscle. I inhaled the smell of burned flesh—my flesh—from the cautery knife. It’s no different from steak on a grill. A few times, my body jerked forcefully on the table. Gloved hands tore apart the muscles of my uterine walls. I heard amniotic fluid splash on the floor and saw my obstetrician dodge out of the way.

A pain in my chest took hold, gradually becoming excruciating. Referred pain is what we call this, caused by upward pressure on the diaphragm from manipulation of the bowel below. It’s no cause for alarm, but it felt as if a vise were being twisted tighter and tighter around my chest. I bore it until I couldn’t, and asked the anesthesiologist if he would help me with the pain. “I can’t,” he said, carrying on with his business. I vomited, regretting the cereal and coffee.

Everyone, correctly, ignored me and my mess; the baby mattered more. On it went, the tugging, the cauterizing, the bodily liquids splashing to the floor, the banter and laughter amongst my operating team. And then, my third child emerged into the world and the searing pain began to subside.

The doctors gave Joe the all-clear. He stood up, peeked over the barricade, and roared, “A girl! Yes!”

He pumped his fists in the air and jumped. I grinned. I hadn’t known he was rooting for a girl.

She was beautiful, far prettier than I had allowed myself to dream of. When I laid eyes on her, I thought, Someone is smiling upon me. Ten fingers, 10 toes, steady breathing, good tone, strong cry, no defects, two small café au lait spots on her thigh—just beauty marks. Phew.

My obstetrician, who herself was nine months pregnant, checked on us in the recovery room. Satisfied, she handed me over to the next team and left.

And so we figured we were done, we happy three. But in the recovery unit, my nurse noticed I was bleeding. Still normal, in the course of things. We thought nothing of it. My nurse changed the bedding beneath me, once, twice. Then again.

My legs were like logs. She moved me in a practiced motion of rolling and lifting, tilting me one way and the other, deftly and discreetly removing the blood-soaked pad from beneath me, folding it in a single skillful move, soiled side in. But I felt fine—happy. If it hadn’t been for the occasional comment from her, I would not have known I was continuing to bleed.

We were the only family in the unit, which was filled with morning sun. How different it was from where I work—the chaotic, windowless, loud, shocking, bare-knuckled display of humanity known as the emergency department. A huge arrangement of flowers stood at the nurses station, gifted by a grateful family. The hospital-ness of the room faded into the background as my husband and I reveled in our new miracle of life.

After my nurse removed the fourth round of sheets, a thought came to me, which I said aloud. “My disability insurance doesn’t cover childbirth.” My husband looked at me curiously.

Unlike me, lying in bed covered in sheets, Joe could see everything the nurse could. He probably guessed why this thought had come into my head. After 13 years of my day-at-the-office stories, he had become a lay expert on medical calamities.

“Your pressure is low,” my nurse announced. It was the first time anyone had acknowledged that something might be wrong.

“Oh, that’s OK,” I said. “I think I’m always 90/60.”

She straightened up. Our eyes met. She was tall and fit, with broad shoulders and intelligent eyes. Energetic, experienced, confident—she was the kind of nurse you want. She looked as if she wanted to say something. But she just continued working.

An hour later, the hamper now full of heavy sheets, the nurse declared, “I’m calling the doctors back.”

The team came, one by one. Each person surveyed the room. Someone readjusted the blood pressure cuff.

The brakes screeched in my head. A transfusion?

“Maybe the cuff is too big,” a resident offered. A nurse went for a smaller one. I laughed. This is my go-to too when the vitals don’t back my own opinion of my patient. Smaller cuff = increased blood pressure … maybe? Someone suggested trying my other arm.

The air grew thinner, like before a storm. The OB resident escalated to her senior, who paged her attending and the anesthesiologist on call. When the anesthesiologist arrived, she looked at me and said, “Your pressure is low, yet you look so well. It must be a side effect of the epidural. Still, can you sign this consent for a transfusion?”

The brakes screeched in my head. A transfusion?

I had never gotten a blood transfusion, yet I’ve ordered it as a doctor with hardly a thought. If my patients are hesitant about getting blood, I have a little speech that comes forth like a cash-register drawer. The chances of getting hepatitis from a blood transfusion are 1 in 25,000. HIV, five times as rare still. The U.S. has the most advanced blood bank system in the world. I had been OK with these odds for my patients, but at this moment they seemed intolerably risky for my own liking. I signed the consent. My body needed blood.

My nurse continued her routine of changing the sheets beneath me. My pressures continued to drift downward. The first unit of blood was hung without fanfare. I watched the deep red liquid snake through the narrow tubing and do a loop the loop before painlessly meeting my arm. It was mesmerizing. I chatted away with the doctors and nurses as if they were my own colleagues, making them laugh with gallows humor. Patients who are doctors themselves make you nervous, I know from experience. But my audience started growing more and more silent.

The anesthesiologist returned. “I don’t get your pressures. They don’t reflect how you look.”

In her defense, I did feel well, even though my blood pressure was abysmal.

“We could put in an arterial line and then we’d know for sure,” she said. She was referring to a small wire with a sensor that gets placed in an artery, a more accurate gauge of blood pressure than a cuff. “But it hurts. I don’t think we’ll do that.”

I disagreed. Just put in the damn line, I thought. She was slight, with brown hair in an unfussy bob. She wore dark tortoiseshell glasses. She moved slowly, catlike, and seemed not too concerned. I worried that she wasn’t more worried. It was the emergency doc in me, always defaulting to the worst possible outcome, I told myself. I reminded myself that this was not my show.

She decided instead to transfuse more units of blood and start pressors, medicines that boost blood pressure. Blood pressure can drop for many reasons—a hemorrhage, an infection, a reaction to medication, a compromised heart. Pressors divert blood to the vital organs, such as the heart and the brain, at the expense of body parts that can be sacrificed, like the arms and legs.

Pressors are the mark of a critically ill patient.

It was easy to doubt that I was sick. For long stretches between the checks by the team, Joe and I were two parents like any other, marveling at our newborn. Even knowing that I had pressors infusing, I wasn’t as worried as I would have been for a patient like me—because it was me. I suspect I didn’t want to see the clinical signs, knowing what I know.

Ben, my 5-year-old son, and Lilah, my 3-year-old daughter, had arrived on the ward to see their new sister. This had been the plan; no one had imagined we wouldn’t be gathering as a family of five. But it was out of the question for them to see me—threaded with lines, infusing with blood, surrounded by beeping alarms, ringed with anguished doctors and nurses. My kids and their nanny set up camp in the waiting room, and my husband shuttled back and forth, acting for them like nothing was wrong.

I wanted to nurse, and asked for my newborn to be brought to me. Funny how powerful the basic maternal instinct is. With my right arm, I nursed my baby while the team tried for a better line on my left in order to hang more blood faster. After many failed attempts by them, I switched my baby to the other breast to free up a fresh arm. The nurse, the one who had first sounded the alarm said, “Dr. Glassman, with all due respect, this is not the time to be nursing.” She lifted my baby—Hannah, we had decided—out of my arms and handed her to Joe.

An authoritative attending had taken over after my doctor left. Dr. P. had dark eyes and long, healthy black hair; she looked young. She told me they would insert a balloon called a Bakri through my cervix and inflate it, to put pressure on the walls of my uterus from within. The idea was to stop the tiny oozing blood vessels by squeezing them, giving the body a chance for its normal physiologic clotting mechanisms to kick in.

Medicine is full of judgment calls based on the best information available in the moment but that can have great consequences.

I was bleeding from where my placenta, now gone, had implanted on the inner wall of my uterus. It had settled unusually, adhering to scar tissue from my past C-sections. In the normal course of things, women stop bleeding after giving birth because the uterus contracts and clamps down on the blood vessels that have supplied the placenta. In my case, the placenta had implanted so low it was beyond the reach of the contracting muscles.

I’ve often wondered whether my first C-section, the one that set me on the course to more C-sections, and now this, had been the right call: When I failed to progress after 24 hours in labor, I was sent to surgery. Was the evidence really so clear that my baby wouldn’t descend, or did they just need me out? Studies have shown that AMA is associated with abnormally prolonged labor, or labor dystocia, which puts the baby and mother at risk. But C-sections also come with their own downsides, including a high rate of repeat C-sections and an increasing risk of significant postpartum hemorrhage and peripartum hysterectomy with each subsequent pregnancy. Medicine is full of judgment calls that are based on the best information available in the moment but that can have great consequences.

Because I had given birth in a teaching hospital, a resident tried the procedure to stop the bleeding first. Learning comes from doing, and the knowledge must get passed on somehow. Forty-five minutes after inserting the Bakri, the same resident carefully removed it. The team held their breath. Not quite half a liter of blood rushed out behind the deflated balloon. Even with my epidural, I could feel clots the size of mangoes passing out of my body.

We have a saying in medicine: All bleeding stops. Either the doctors get control or the well runs dry. It was now an open question as to which category I’d find myself in.

It was about then that I noticed that the sites where the nurses had tried to insert the lines had started to well up. “That’s interesting,” I said, part jester, part doctor. “I hope I’m not going into DIC.” I said it lightly, but I was thinking to myself, Wouldn’t that be a scream? I looked at Dr. P. With one hand obscuring her lips, she spoke quietly with an older doctor, the éminence grise of the department, who had recently been summoned to help with my situation.

Disseminated intravascular coagulation is a state in which the complex processes of blood clotting run amok. We need our blood to clot; otherwise, we could bleed out from a minor injury. But in DIC, your blood begins to clot in spots where it should run smoothly—inside your arteries and veins—and you bleed unchecked in places that should be clotting, like fresh wounds. This can happen after a large hemorrhage, in major trauma, during an overwhelming infection. Women who have significant obstetric complications are at risk for DIC.

DIC is dire. My joke landed like a lead sinker because it wasn’t a joke at all. I was going into DIC. This was the moment of recognition for the room, when everyone grasped the full situation.

In medicine, the picture often changes incrementally. It can be hard to recognize the instant when a patient has crossed the line from stable to unstable, or from unstable to gracing death’s door, because there are no clear lines. It’s one thing when someone bursts through the ER doors pale, dripping in sweat, and clutching their chest; it’s another when a patient has been under your care for hours with an inscrutable diagnosis and no overt signs of deterioration, just subtle changes in vital signs or new beads of sweat on their brow. You could be forgiven for not apprehending the exact moment when an ember became a raging wildfire.

The number of people in the room had swelled. Nurses, techs, OB residents and attendings, anesthesiologists, and Joe, with Hannah tucked against his chest in a warm football hold. They were all looking at me, serious and worried.

I‘ve been in this spot myself. Usually it’s with a young patient who doesn’t feel well, in an unspectacular way, and who doesn’t trigger the standard metrics used to identify someone as “sick.” I keep an eye on them while awaiting results, but I’m really more focused on my other patients. In time, the severity of their illness unveils itself. They become the sickest person in the room, the one you desperately need to save because a young adult in the prime of life should not die. In these situations, I berate myself, thinking, I should have seen this sooner. My heart pounds, and I am burning to save them and full of guilt.

Trying to break the unbearable heaviness in the room, I raised my voice. “Dr. P.,” I said, “don’t you hate it when you walk into a shift and get handed a train wreck? I know I do.” Everyone laughed. Even Dr. P., who had been stone-faced, gave a half-smile. Humor is good in a moment like this. How I was possibly dying and well enough to make jokes is hard to explain. Perhaps it was the endorphins from my new baby. Or maybe women are simply designed to handle incredible bodily insults around childbirth.

By this time, the nurses were quickly trading out the spent bags of blood with new ones, placing them in pressure devices to make them empty into my body faster. Behind my bed, a cacophonous installation of medicine pumps, fluids, tubing, monitors, wiring, flashing lights, and units of blood took shape, so familiar to me from my own critical patients. Meanwhile, Joe was unconsciously stroking Hannah’s head like a good luck charm, trying not to get in the way. His mouth taut, he occasionally grasped my fingers. He stayed quiet, knowing that it was best to leave this to the professionals.

It must have looked like chaos, but I knew it was actually everyone working together like rowers on a shell, trying to outpace the boat with the angels of death. Finally, Dr. P. said to me, “Nothing is working. We have to go back to the OR.”

My monitor read 63/17, even on pressors. If I had been my own doctor, I would have swallowed hard. I was in hemorrhagic shock, a state in which oxygen-carrying blood can’t adequately perfuse the body’s vital organs. Lacking oxygen, cells die off, triggering a massive inflammatory response. The body tries to restore the proper environment with rapid breathing and a racing heart. If the bleeding isn’t stopped and the blood replenished, the whole system goes into an irreversible nosedive. One by one, the organs of the body shut down.

I began to heave. I desperately wanted the head of my bed lowered and asked the nurses to do so. Lying flat eliminates gravity and allows blood to flow to the brain. If there was any chance of salvaging me, it would have to happen soon. The team members hastily began “packaging” me: untethering me from the scaffolding, throwing what was critical onto the gurney. They yelled ahead to clear a path and began the sprint to the OR. It was all familiar—with the exception that I was the one in the gurney.

They slowed down for a few seconds to let me say goodbye to Joe and Hannah. Joe’s eyes said, Fight. He squeezed my hand. I stroked the impossibly small toe of my more-beautiful-than-expected baby.

I could feel clots the size of mangoes passing out of my body.

“I’m sorry, Joe. Tell Ben and Lilah I love them.” I had pushed for this child. I could have been content with two, but that wasn’t enough. I’d wanted one more. I’d misjudged my invincibility.

“Take care of them,” I said. I managed a smile, and the gurney started moving again.

I felt gray and empty. This must be the feeling, I realized, of life trying to leave you. Watching someone, it’s hard to predict when that exact moment might start. But doctors see it unfold: The patient loses consciousness, their heartbeat slows, and the march toward death begins. When this happens on my watch, I spring into action while muttering to myself, Fuck, no.

Now the diminished blood flow to my brain made it hard to think. Nothing to do but remain calm. I’m sure they know they need to hurry.

My doctor was running next to my gurney. I found her hand and said, “Dr. P., please, do everything. For my kids.” I was shocked to see her wipe away a tear.

They raced me to the OR and prepped me for surgery, again. Someone put an oxygen mask over my face. It was my last chance to say anything and, I knew, perhaps my last-ever glimpse of life. I must make them understand I have a family to get back to, I thought. Marshaling the last bit of energy in me, I took my mask off and spoke to everyone in the room. “Please. I need your A game. Not for me, but for my babies.”

Perhaps it was silly. But I didn’t think it would hurt to press the point.

The rest was oblivion. There were two teams of obstetricians and an extra anesthesiologist, I would later learn. Into my jugular they hastily inserted a line the size of a small hose to run the blood in faster. They removed my uterus, but because of the DIC, I continued to ooze everywhere. Clotting and bleeding in all the wrong places. They called the blood bank and sent runners for more.

With my team watching over me in the OR, I lay with my incision open, my abdomen packed with bandages, while the blood products flowed in. They waited. And waited. If I was continuing to bleed internally, they didn’t want to suture my abdomen together only to have to reopen me again later. When they were fairly certain that I had stopped bleeding, they removed the packing and closed.

I had lost about 6 liters of blood that day. A woman my size has only about 4.5 liters in total. I had lost my body’s entire store of blood, plus a third more. As quickly as they were giving me blood, it had been running out of me.

All told, I got 19 units of blood, 11 liters of IV fluids, and an assortment of other blood products that are depleted in DIC. Nineteen units is an impressive number, to me at least, as an ER doctor. Maybe surgeons see worse. I once gave 11 units to a man bleeding from liver failure, hoping to keep his heart beating long enough for his family to say goodbye. He died a day later.

I woke up late that night, intubated and in the surgical intensive care unit. I don’t remember this part. A tube had been placed through my vocal cords, and the ventilator was pushing breaths into my lungs. With that awakening, everybody breathed a sigh of relief. My behavior, my vital signs, my bloodwork, the fact that I was making urine: It all augured well. No stroke, no heart attack, no kidney failure, no respiratory failure, and blessedly, no more bleeding. A miracle.

I spent that night in and out of consciousness, with the endotracheal tube in my throat. In my clearer moments, I thought, Shit, I’m intubated. Intubation is a medical breakthrough that has saved countless lives. I had intubated so many. Never had I imagined that I would be intubated myself. What’s not taught is that it hurts, as if a little creature is furtively rubbing your vocal cords with sandpaper. I kept my neck perfectly still to reduce the red-hot pain.

Because I couldn’t speak, I wrote (or so they told me). Most of the writing was unintelligible, like the scribble of someone deeply intoxicated. I have kept this piece of paper, folded neatly, in my bedroom drawer. To Joe, I wrote clearly:

You are a mensch. Get a drink.

What’s my BP? How many units? DIC???

Ben. Lilah. Hannah? LOVE.

I was famous for a few minutes in that vast hospital, the doctor-patient who had miraculously pulled through. Why had I made it when another woman my age might not have? I’m not sure, but I can guess. For starters, my biological age—a measure of how well our cells are managing the cumulative effects of time—turned out to be younger than my chronological age suggests. I was healthy going into the surgery, and I had no comorbidities (like diabetes or heart disease) that would have made it even harder for my body to hang on until my team got control. Moreover, those on my team acted well and acted fast. They replenished the blood and blood products that were necessary to right the ship and reverse the DIC. And they addressed the source of the bleeding—they got rid of my uterus.

But mostly, I got lucky.

After I stabilized and my breathing tube was removed, a revolving door of visitors came to me, people who had worked on me in the OR. “I wanted to see you,” they said. Over and over, I told them thank you. Apart from a few small detours, including a shell-shocked bowel that took an alarmingly long time to get going (what we call an ileus—I’ll never make light of that diagnosis again), my recovery was rapid. Five days later, on a beautiful, cloudless day, I walked out of the hospital, carrying Hannah in her car seat.

She’s 9 years old now and, like my other kids, a constant source of both joy and worry. In the immediate shadow of that experience, I drank in the pleasure of being alive. I had about six months of solid euphoria. After that, it was an inevitable stepwise return to the everyday stuff of living. I went back to work, and life resumed. I accepted, even welcomed, the return to the banal. It’s what I fought so hard to survive for.

Dr. Sarah Adams is a scientist and science communicator who makes complex topics accessible to all. Her articles explore breakthroughs in various scientific disciplines, from space exploration to cutting-edge research.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/The-Best-7-Day-Walking-Plan-for-Insulin-Resistance-8cf4c8a8c16e4dddac34d5d97633e91f.jpg)