Stacey Lott was in Los Angeles on September 11th, a continent away from the World Trade Center when the terrorists flew two airliners into the Twin Towers.

Yet toxic dust from Ground Zero is slowly destroying her kidney.

The Sussex County woman recently donated it to childhood buddy Michael Megna, a first responder who spent three weeks at the site looking for survivors. Several years after the terror attack, he developed an extremely rare kidney disease that forced him to onto dialysis.

It has been yet another blow for Megna, 52, who continues to battle to get compensation from the September 11th Victim Compensation Fund. In 2016, at the peak of his frustration and with his West Milford home in foreclosure, he took out a billboard on Rt. 3 begging officials to “Do right by Mike.”

An impatient man by nature, he has spent the last two decades trying to master patience.

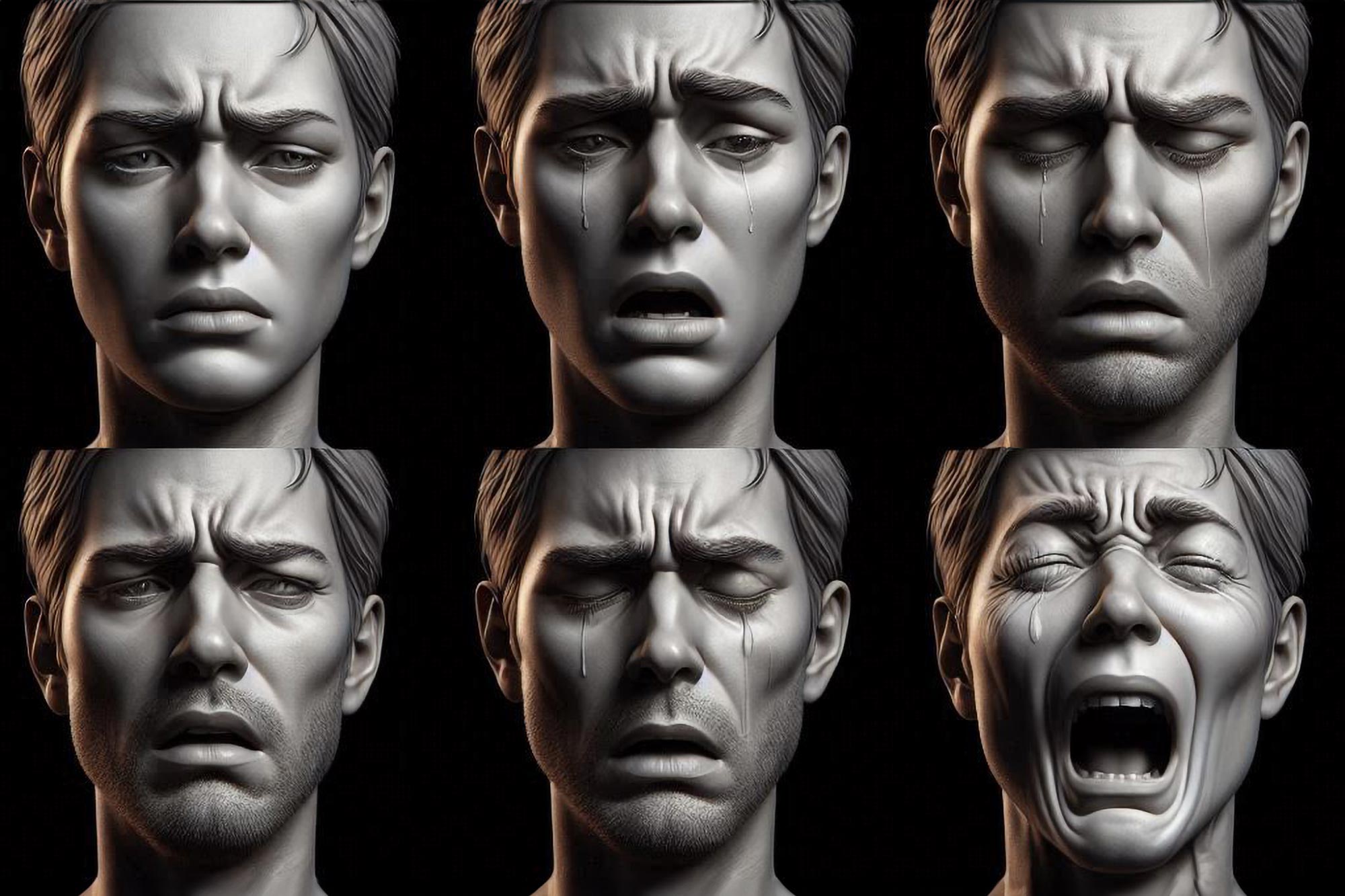

“I had explosive rage and would break things, like a windshield…and doors and walls and tables and lamps and knuckles and hands,” he said recently. “I will never be that guy again.” At one point he’d been so disruptive at the Rutgers-based clinic that treats New Jersey’s 9/11 health victims that he was banned from future visits unless accompanied by his brother.

Megna and Lott grew up in Mt. Olive; their brothers were best friends, their families attended St. Jude Thaddeus R.C. Church together. They hadn’t seen each other in years until 2022, when they crossed paths at an informal high school reunion at a local tavern.

She heard his hard-luck tale and blurted out that if he really needed a kidney, he could have hers.

“And I meant it,” she said recently. “It was God’s way of intervening — it was meant for me to be there.”

And as if her role as Megna’s savior were destined, her blood type was the requisite O-positive.

The transplant took place last December, and for several weeks all seemed well. Late in February, however, Megna’s team of doctors at Cooperman Barnabas Medical Center in Livingston stopped by on morning rounds to deliver awful news:

Like something out of “The Terminator,” his relentless disease appeared to be back at work. Having destroyed his kidneys, it was now attacking Stacey’s.

Megna wept while a nurse silently stroked his hand.

“It broke my heart to tell her,” he said of Stacey. “She didn’t give me a car, she gave me a body part! My only job was to take care of it.”

As for Lott, she is saddened for Megna’s sake. “The hope was this would be the cure to help him have a productive life,” she said. Despite this setback, she said she does not regret her donation: “It got him to a better place.”

At Ground Zero

Megna was a Pompton Lakes police officer on the day of the attack. His father was a Port Authority police officer, and when he and his brothers couldn’t reach him that morning, they headed to Ground Zero to find him.

Father and sons were safely reunited, but for the next three weeks, Megna returned nearly every day to man the “bucket brigade,” clearing debris in hopes of finding survivors. He was a healthy, robust 29-year-old Marine veteran.

Six years later, blood appeared in his urine.

By 2019, he needed dialysis.

On paper, Megna’s disease looks like an aberrant Scrabble hand: Atypical anti-glomerular basement membrane (anti-GBM) nephritis. Neither a cancer nor a conventional autoimmune disease, it originates in the bone marrow. His produces a renegade protein that attacks the very kidney filters designed to snag toxins, said Stephen Erickson, a nephrologist at the Mayo Clinic whom Megna consulted eight years ago.

The overall disease strikes one in a million people. Megna’s slow-moving variant is even rarer, affecting one in 10 million.

As one of his doctors put it, “There’s rare, there’s super rare, then there’s you.”

That rarity makes it nearly impossible to run the comparison study needed to qualify for a payment under the James Zadroga 9/11 Health and Compensation Act, passed by Congress in 2010 and renewed after public pressure in 2019.

The act spells out the mandatory process to get an illness added to the list of “covered conditions” as they continue to emerge years after the terrorist attack, said Benjamin Chevat, executive director of 9/11 Health Watch. That non-profit advocacy group, founded by the unions whose members participated in the emergency response and lengthy clean-up, helped write the law.

The federal government will pay for treatment and compensation for an illness only if research determines the 9/11 people – first responders, residents or workers in Lower Manhattan– develop it at a higher rate than the general population.

For common diseases that emerged fairly quickly – asthma and sleep apnea, for example – it was easy to meet that requirement. Cancers were slower to develop, but eventually nearly all of them were added to the list.

In the case of Megna’s one-in-ten-million illness, the regular way to get on that list is blocked, for hardly anyone in the general population gets the disease. And those lawyers who advertise on television? They’re interested only in people who have covered conditions, Megna said.

Yet Megna may have reason to hope, said Iris Udasin, Medical Director of the World Trade Center Clinic of Excellence at Rutgers University’s Environmental and Occupational Health Sciences Center.

The clinic monitors or treats about 5,000 New Jersey residents who were near Ground Zero that day. They don’t treat Megna’s kidney disease – because it isn’t a covered condition – but Udasin is very familiar with his case and does monitor his other ailments. (“As far as poor Mike is concerned, I treat the things I can treat,” she said.)

She and her fellow researchers hope to use a novel argument that succeeded just last year in getting uterine cancer covered. It, too, was rare among 9/11 survivors and first responders, simply because only a quarter of that group is female.

Researchers overcame that obstacle by citing “biologic plausibility,” Udasin said. They argued certain chemicals, called endocrine disruptors, can cause uterine cancer. Those chemicals were in the witches’ brew of dust at Ground Zero. Therefore, it was entirely plausible they were to blame for the uterine cancers seen in the 9/11 group.

That same approach could work for Megna’s disease, she said. It has long been linked to exposure to hydrocarbon solvents, which are petroleum derivatives. Many of the documented cases involve auto mechanics who worked in repair shops, and the condition has been induced in lab rats by exposing them to gasoline fumes.

Those very chemicals were in the smoldering debris of the collapsed Twin Towers.

Udasin confirmed there are now other patients in the WTC Health program who report having the same ailment. (She isn’t comfortable giving an exact number.) Research out Mt. Sinai Medical Center’s 9/11 clinic has turned up 11 people with illnesses affecting the kidney filters. Citing those patients would bolster the case such illnesses were caused by exposure at Ground Zero.

However, each of those self-reported cases must be confirmed by examining medical records, including lab or biopsy results.

That’s a laborious task that will take time.

“The good news is there is reason to hope there’s a pathway. The bad news is it takes a long time to do this properly,” Udasin said. She didn’t want to hazard a guess of its completion date.

Squeezing research

In much the same way a town road department plows the main streets before plowing a little cul-de-sac, so 9/11 researchers have tackled illnesses affecting the most victims. And they’ve had to squeeze research in-between their main task of treating their patients.

If she had a bigger budget, Udasin said, she could hire more people to compile the data.

Megna, who served a combat tour in the Marine Corps in Desert Storm, is financially stable these days. He is on full disability from the U.S. Veterans Administration because of PTSD, migraines and tinnitus, and also receives a monthly check and free medical treatment from New York State Workers Compensation because of his time at Ground Zero. He and his girlfriend own a home in Mt. Olive.

But his inability to get compensated for his illness is a perpetual source of bitterness. He said he would view a one-time payment, likely to be about $250,000, as validation of the life-altering damage that fateful day inflicted on his health.

In the meantime, he’s on steroids to suppress his immune system – a dose so high his hands tremble. He has endured sessions of plasmapheresis, a blood-cleansing process that left him exhausted. He can barely walk up a flight of stairs. He’s heartbroken that his daughter, the youngest of his three kids and the one born after 9/11, has never seen him healthy.

And he’s just starting to come to grips with the reality that what he hoped would be a cure now looks like it won’t be, and that more treatment may be in his future.

When doctors performed the transplant last December, he said they indicated there was only a very slight chance his disease would reappear. The following month, a paper in the The American Journal of Transplantation detailed six cases in which the disease had resumed, all within a span of one to seven months after transplant surgery.

“I want them to fix me,” Megna says, “but there is no true solution.” He knows they scour the latest medical literature about his obscure illness on their own time, searching for answers. He’s grateful for their efforts, yet said he feels like a guinea pig.

The ultimate solution for Megna might be a stem cell transplant, said Erickson, the Mayo Clinic nephrologist. That would entail eradicating his defective bone marrow via chemotherapy, then giving him donor stem cells that would form new marrow. Until the underlying problem in the bone marrow is addressed, transplanting a healthy kidney has little rationale for people with this disease, Erickson said.

In a rare turn of good luck for him, Megna’s subtype of the disease is slow-moving, so its recurrence hasn’t plunged him into an immediate medical crisis. Yet once again, the clock is ticking for his new kidney.

Learning that researchers have begun work on getting his disease added to the compensation list is heartening to Megna – yet only slightly. It leaves him right where he’s been for nearly 23 years: waiting.

“I get it, that it’s going to take time,” he said. “But I don’t really know how much time I have.”

His predicament is aptly summed up by Chevat, of 9/11 Health Watch: “The speed of health research is not the speed of people’s lives.”

Kathleen O’Brien is a freelance writer who covered health for NJ Advance Media.

Rachel Carter is a health and wellness expert dedicated to helping readers lead healthier lives. With a background in nutrition, she offers evidence-based advice on fitness, nutrition, and mental well-being.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():focal(753x293:755x295)/Brooke-Shields-061624-5288dd6fc7fe47729ea714323971d815.jpg)