This is part of Opening Arguments, Slate’s coverage of the start of the latest Supreme Court term. We’re working to change the way the media covers the Supreme Court. Support our work when you join Slate Plus.

If there were any doubt about the Supreme Court’s commitment to the conservative project of bringing about the “deconstruction of the administrative state,” this term will likely lay those to rest. The court has already teed up several potential blockbusters for decisions by the end of June, including two cases that could spell the end of the Chevron deference doctrine and another that could significantly restrict agencies’ ability to use administrative law judges in enforcement proceedings.

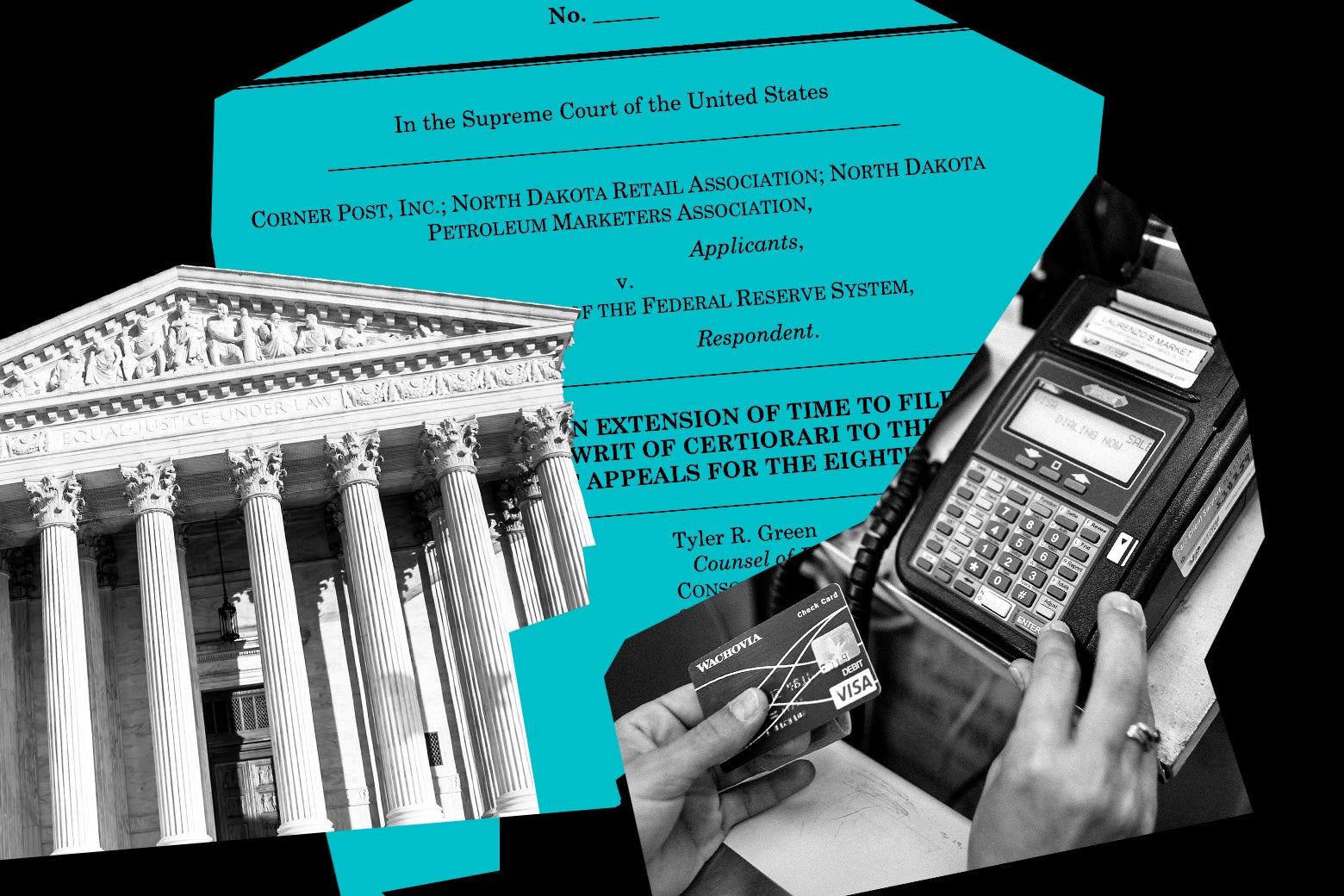

On Tuesday, the court’s conservative supermajority will get to take yet another powerful swipe against the administrative state when it hears oral arguments in a case called Corner Post v. Board of Governors. Despite the very real threat it poses, this case has received surprisingly little attention.

At issue in Corner Post is a technical debate over who is eligible to bring lawsuits against the regulations that agencies issue. The Administrative Procedure Act, which establishes the general framework for challenging the legal validity of a regulation, provides a statute of limitations of six years after the claim “first accrues.”

The prevailing understanding of that language—and frankly, the obvious one—has been that such claims “accrue” when the rule being challenged is first issued. But the corporate litigants in Corner Post (with the support of a conservative legal advocacy firm) aim to jettison that objective benchmark. In its place, they hope to create a new, free-floating rule that ties the start of the statute of limitations to when the particular challenger involved first “suffers legal wrong.”

The case centers on a 2011 rule issued under the Dodd-Frank financial reform law that sets maximum “swipe fees” that banks can charge for the use of their debit cards. The rule survived an initial challenge when it was upheld by the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals in 2015. Apparently dissatisfied with this outcome, two trade associations representing convenience stores and gas stations wanted a second bite at the apple and so initiated this case in 2021—a decade after the rule was first issued.

The Federal Reserve, the agency that issued the rule, sought to have this second suit dismissed as barred by the APA’s statute of limitations. Remarkably, the trade associations responded by adding an individual gas station called Corner Post as a co-plaintiff. The twist? Corner Post first opened for business in 2018. That was the moment when the store’s claim against the rule “accrued,” according to the trade associations, which meant that the statute of limitations was still open to them.

These facts illustrate how this new interpretation of the APA’s statute of limitations is a recipe for the exact kind of legal uncertainty that conservatives claim to hate. Any rule—no matter how old—would be potentially subject to a nonstop conveyor belt of litigation. All an opponent of a particular rule would need to do is find a relatively new business that is subject to the rule’s requirements. Better still, they could even manufacture fictitious new “companies” for the sole purpose of bringing lawsuits. In many cases, this strategic behavior would complement the blatant forum shopping that corporate interests and conservative legal advocates already use.

What little attention Corner Post has attracted so far has tended to focus on its potential to amplify the chaos that would ensue if the court ends up overruling the Chevron deference doctrine in the pending cases Loper Bright v. Raimondo and Relentless v. Department of Commerce. The end of Chevron deference by itself could reopen hundreds of prior cases that had been resolved using the doctrine. If the court were also to adopt the trade associations’ new formula for calculating the statute of limitations under the APA in Corner Post, that would add more fuel to this blaze of litigation. This new loophole in the statute of limitations would empower industry to reach back further in time and reopen an even larger universe of old Chevron deference cases.

Importantly, though, the significance of Corner Post extends well beyond traditional Chevron cases, which involve challenges to the statutory authority for particular regulations. It would also allow corporate interests to relitigate disputes over the underlying policy rationale for old regulations they oppose—generally referred to as “arbitrary and capricious” claims. Creative industry and conservative movement attorneys would be presented with a huge legal target to aim at when challenging existing regulations.

Indeed, it is this wide-ranging retrospective reach that has conservative opponents of the administrative state most excited about the prospects of a win in Corner Post. As it stands, they have already devised effective strategies for blocking the flow of future regulations. For instance, the campaign to end Chevron deference is an important part of this broader plan (though, as noted above, it would have some retrospective effects as well). The conservative legal movement is betting that risk-adverse agencies will respond to the heightened threat of judicial second-guessing over their decisionmaking by significantly scaling back the ambitions of their future rules—or perhaps even by abandoning some of their more far-reaching rulemakings altogether.

What remains unrealized, even with the end of Chevron, is their vision for dismantling that body of rules already on the books. One of the major lessons of the Trump administration is that removing them one by one through the standard rulemaking process is slow, resource-intensive, and legally fraught. Instead, they have found it far more efficient to use the wrecking ball of litigation to knock down the existing regulatory edifice. The promise of Corner Post is a wrecking ball with far greater reach.

By the end of the current term, the Supreme Court could hand to regulated industries and conservative legal advocates powerful weapons for unwinding America’s regulatory past while throttling our regulatory future. This one-two punch against the administrative state would decimate a critical part of our constitutional democracy while leaving tens of millions of Americans at unacceptable risk of harm from pollution, workplace injuries, dangerous products, and much more.

Jessica Roberts is a seasoned business writer who deciphers the intricacies of the corporate world. With a focus on finance and entrepreneurship, she provides readers with valuable insights into market trends, startup innovations, and economic developments.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/24016883/STK093_Google_06.jpg)